* Warning – contains spoilers. * Please only read this if you have finished all three books of the Trilogy.

The narrative of the Kästner and the Nussbaum families ends on the last page of The Turn of the Tide, the third and final book in the Sturmtaucher Trilogy, on the 17th August 1945, although the epilogue provides a short summary of how the members of both families fared in the years following the horrific aftermath of the Second World War.

But I didn’t expand on what happened to those other characters, good and bad, who also had a part to play in the harrowing journey the two families faced from Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 to the Nazi’s defeat in 1945. This post is about the justice served after the war was over, and about some of the characters lives, both real and imagined in the decades following the cessation of hostilities.

A series of war crimes trials took place in Germany, and elsewhere, in the years after the war. The principal Nazi party leaders who survived, and were captured, were tried at the Nuremberg trials, although the whereabouts of a number of the most heinous war criminals remained a mystery, some forever, others for years after the war ended. Muller, the Gestapo chief, Eichmann and Josef Mengele were unaccounted for – Eichmann famously was located in the late 1950s after a tip-off from a German prosecutor and was smuggled out of Argentina in 1960 to stand trial in Israel. He was sentenced to death in 1961 as one of the main architects of the Nazi’s Final Solution.

Mengele lived out the rest of his life in Argentina, then Paraguay, and finally Brazil as investigators tried to find him. He drowned in 1979 but his death remained a secret for a decade or more, and the remains weren’t confirmed as Mengele’s by DNA until 1992.

There were a number of smaller War Crimes Trials, but these dwindled out as it became more important for both the East and the West to allow both of the new Germanies to function as nations, albeit under the military occupation the victors, and most protagonists of the Holocaust, and almost all of their supporters and sympathisers, escaped Justice. In addition, for the bulk of those who were convicted, and given long sentences, early release became the norm and, apart from a few high profile prisoners, there no former Nazis in prison by 1960, the year of my birth, only 15 years after the end of the war.

Historical figures.

There were many real characters in the sturmtaucher Trilogy, and I tried to write them pretty much as history presented them, although I obviously fictionalised their interactions with the Kästners and the Nussbaums, and the other fictitious characters in the books.

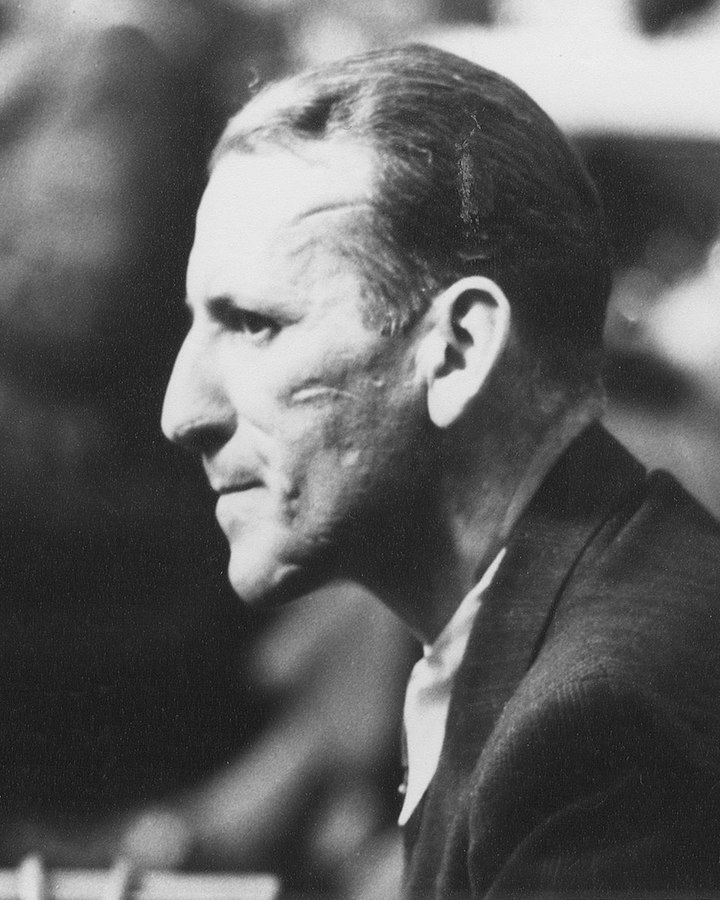

Of all these real-life people I used in the books, Wilhelm Canaris was by far the most integral to the story and, if you haven’t read the trilogy, the remainder of this article most certainly contains spoilers. For those who have read the books, you will know Canaris’s fate, but it is worth mentioning how he is considered by history. He was a controversial character and his initial support of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist Party (the NSDAP) was tempered by his gradual realisation that Adolf Hitler was both mad and extremely dangerous for Germany and for Europe, and that the war, and latterly the persecution of Europe’s Jews, should be stopped by whatever means were available to him. It is not known for sure that he was an integral part of the almost successful attempt on the Fuhrer’s life, but it was his connections with the plotters that ultimately sealed his execution three weeks before the end of the war.

In an interesting adjunct, Erica Canaris, his widow, received a widows pension for the rest of her life from Franco’s Spanish government, presumably in recognition of Canaris’s pivotal role in keeping Spain out of WW2.

Of the main Nazis who lived and worked in Kiel, Obersturmbannführer Friedrich (Fritz) Schmidt, Kiel’s Gestapo chief, and the man who built the Nordmark worker’s “education camp”, survived the war, and, under a false name, worked first as a construction worker in Munich, then as a clerk and finally manager for the regional government. His real identity was discovered in 1961 and he was given a short prison sentence for the deception, but did not serve it. He was arrested again in 1963 and convicted of complicity in the murder of four allied officers in 1944. He was released after two years, and returned to work. In 1968, he was re-arrested for his part in the murders, and served another year in prison. He died shortly afterwards.

The man he appointed Kommandant of Nordmark, Sturmbannführer Johannes Post, was tried and executed in 1948, not for his crimes at Nordmark, but for his part in the killing of the same group of Allied airmen that Schmidt was later tried for.

By the time of Post’s trial, the efforts of the war crimes tribunal in the British sectors was largely geared to prosecuting Nazis who had committed war crimes against British and Commonwealth subjects, a policy expediated by the need to have West Germany as an ally against the growing threat of expansion of communism and the Soviet Bloc.

Hinrich Lohse, the Oberpräsident of Schleswig-Holstein and the Reichskommissar for the Ostland, was the top Nazi in control of the most Northern of the German provinces and the occupied Baltic States. Despite overseeing the slaughter of almost all of the Jews, Romani Gypsies and Communists in the areas under his control, he escaped the death penalty and only served 3 years of a ten-year prison sentence due to illness. He lived as a free man for a further 13 years.

Lise Mey, a staunch Nazi supporter and the daughter of Beate Böhm, and the Kästner’s neighbour, is one of the more colourful fictional characters in the trilogy, but three of the many high ranking Nazi lovers she took were real historical figures:

The first of those, Heinrich Himmler, committed suicide in prison after being captured by the allies by biting down on a cyanide capsule when medics tried to examine his mouth, and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, another of her lovers, was captured shortly after the war in an alpine lodge high in the mountains, trying to escape southwards through Switzerland and Italy. He was the highest ranking SS officer to face trial and was executed in 1946.

SS-Gruppenführer Otto Hofmann, the third of Lise’s senior Nazi lovers, was responsible for organising testing for racial selection in the territories occupied by Nazi Germany. He was also a participant at the Wannsee Conference, where the Nazi’s Final Solution to the Jewish Question was ratified. During the war, he was transferred to Stuttgart as SS and Police Leader for South-Western Germany.

In March 1948, Hofmann was tried for his actions as chief of the Race and Settlement Main Office and was sentenced to 25 years in prison for Crimes against humanity and War Crimes but, on 7 April 1954, he was pardoned and released from Landsberg Prison. He worked as a clerk until his death in 1982.

In a fictional aside, at the end of the Trilogy, we find out that Lise has attached herself to an American Major who was besotted by her looks and her sexual allure. I’m sure Lise Mey would have made it to the states and, after divorcing the unlucky major, would have found herself a rich, older husband and a series of lovers, living to a ripe old age, pining for the glory years of National Socialist rule, and for the return of Adolf Hitler as leader, whose death she quite never believed.

Captain Wheatley, the Army lawyer who investigated the Cultybraggan murder of Feldwebel Wolfgang Rosterg, which actually took place at the POW camp in Comrie, went on to become Lord Wheatley. In the books, I wrote Axel Langefeld and Gerhard Schlesinger as part of the group found guilty of the German prisoner’s murder. In real life, five Nazi prisoners, the oldest being twenty-one, were executed at Pentonville prison in 1946 for the crime.

Doctor Kate Hermann, the physician who treated Franz’s injuries in hospital, and saw the first spark of his recovery, was real. She was a Jewish refugee who arrived in Britain in 1937 and was the first female neurology consultant in Scotland. She retired from medicine in 1970 and lived to see the re-unification of Germany, passing away in 2007, in her nineties.

Fictional Characters

After five years, and over a million words, I came to think of my fictional characters as real people, even those who only played a peripheral part in the story.

One such group were Børge Lund and his family, and his friends, who helped the Kästner brothers and the two young Nussbaums during their voyage of escape. As part of the Danish resistance, their lives would have been constantly at risk, but I like to believe that they would have survived the war.

Because of the rescue, and of the following Danish efforts to obtain the release of the Danish Jews who were the Theresienstadt concentration camp, over 99% of Denmark’s Jewish population survived the Holocaust.

As part of the organisation who rescued their country’s Jews, Børge and the others would have been among those honoured for their collective heroism by Yad Vashem in Israel as being “Righteous Among the Nations.”

Captain Andrew Stanworth and Sub lieutenant Graham Archibald, of HMS Intrepid, the Destroyer that intercepted Der Sturmtaucher as it entered British waters, were both fictional, but their stories had a ring of truth to them. Most officers commissioned in the Royal Navy during the war came through the ranks of the Royal Naval Reserve (professional seamen), or the Royal Naval Voluntary Reserve (civilians with no experience, trained first as seamen, with some going on to be officers.)

An intermediate form of reserve, between the professional RNR and the civilian RNVR, was formed in 1936. This was the Royal Naval Volunteer (Supplementary) Reserve, open to civilians with proven experience at sea. By September By 1939, there were over 2000 RNV(S)R members, mostly yachtsmen, who were recruited for active service after a 10-day training course, joining their colleagues from the RNR and the RNVR. Some went on to command vessels, mostly coastal and auxiliary, but a few advanced to command larger naval ships. Almost all were demobilised after the war.

A number of famous public figures came through WW2 with the RNVR, including two of my favourite writers: Nicholas Monsarrat, frigate commander during World War II, and author of The Cruel Sea, reached the rank of lieutenant commander. Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, served in Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, and reached the rank of commander. Both used their very different wartime experiences extensively during their literary careers.

I’d like to think that, after the war, Franz and Johann would have looked up the Captain and the Sub-lieutenant of HMS Intrepid to thank them for the way they they’d been treated, and because they’d spared Der Sturmtaucher from her fate as gunnery practice.

I would also have hoped that Johann would have managed to explain his actions to his friend, Lieutenant Maximilian Grabner, and that ‘Maxi’ would have come to forgive him. As for Colin McLeod, I’m sure that the injured merchant seaman and Franz Kästner, the German soldier he befriended, would have continued their acquaintance in Scotland when Franz (or Frank as Colin knew him) returned to Oban to live with Ruth and his new family.

The Weissbergs, who accepted Ruth and Manny as part of their family during their internment on the Isle of Man, and in Finchley after their release, would have stayed in touch with the young Nussbaums, and I can imagine Aaron, Gella and their children would have spent many holidays on the West Coast of Scotland with Ruth and Franz.

With Heinrich Güllich, dead, Carl Meyer, his fellow Gestapo officer, was the most evil survivor of the war, and although in prison, he would have likely have been released during the decade following the end of the war. I suspect he would have finally made the journey across the border to East Germany, and may have found a use for his particular talents in the Eastern Bloc country’s dreaded security services, as a Stasi officer. Like many former Gestapo or SS members, punishment was often a secondary consideration to the need for experienced security personnel, on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Finally, Gus, the elephant seal, watched by Erich Kästner and his daughter Antje at Hanover zoo in 1942 as their world collapsed around them, was a real character. Those of the Zoo’s animals that weren’t killed by the intense bombing of Hannover were evacuated to safety but, sadly, few survived the war, often becoming food for the starving hordes during the destruction of Germany in 1944-45.

I’d like to think that Gus was the exception.

Thanks for all that info Alan. Some of the real Characters I knew about their fate but not all.it was really worth a read

Thanks for the feedback, Louise. A few readers had asked about the non-fictional characters I had used, so I thought it was worth doing a post, although I was worried about spoilers, but it is well flagged enough, I think.

Brilliant post, Alan, enough information without becoming brain overload.

Thanks, Sally.

Slowly but surely you are improving my education.

Thanks 😊

Sorry, missed this. I also learned a hell of a lot researching the books.

Saw your article on FB regarding the Girvan Lifeboat and from that I downloaded The Stürmtaucher Trilogy which I have just started reading and which I am enjoying immensely.

By the way, my grandfather, Robert Ingram, Bobby served with the lifeboat from 1930 to 1952, initially as Bosun and then Coxswain.

Thanks for getting in touch, Robin. Fascinating about your grandfather – there are quite a few Ingrams still in Girvan today. Cheers for reading the books – I hope you continue to enjoy them. Let me know what you think when you finish. All the best.