After penning three crime novels, the last of which was incredibly well received, I should have continued writing in the crime genre, one per year perhaps, to capitalise on my growing readership.

But I’m a keen sailor, piloting my 45-year-old yacht around the west coast of Scotland and the Irish Sea and, because writing what you know about always seems a good place to start, I felt compelled to publish a book where sailing played a prominent role. I did consider a murder investigation connected with sailing and the sea, and one day I might come back to that concept, but a germ of an idea had wormed its way into my head, and I couldn’t shake it loose.

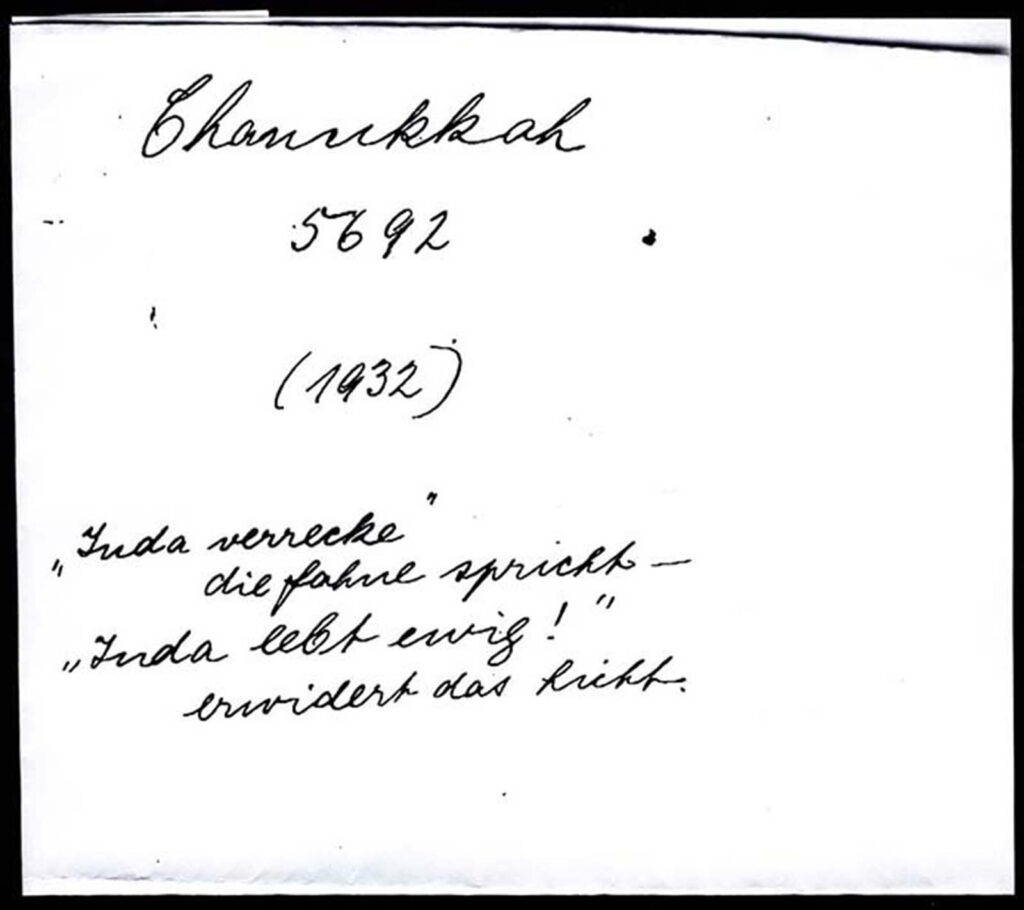

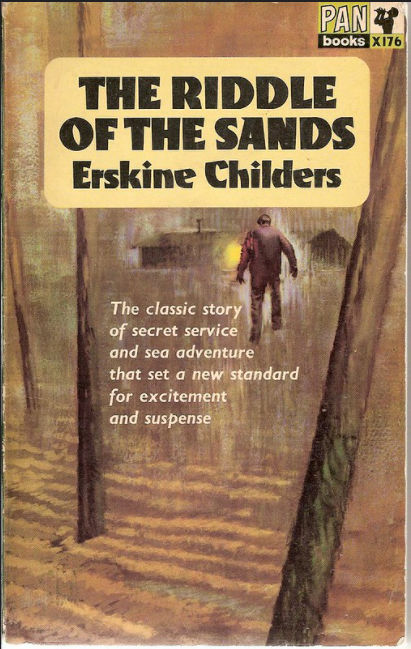

I’d read Erskine Childers’s The Riddle of the Sands as a teenager, and in a way, it was his description of the very ethereal sailing among the tidal mudflats and low islands of the North Sea coasts of Europe in the creeping disquiet just prior to the First World War that intrigued me, but I’d also read numerous books about the Second World War, including many harrowing stories about the Holocaust, both fact and fiction, and a jumble of ideas swirled around in my head, eventually congealing into the narrative that became the Sturmtaucher Trilogy.

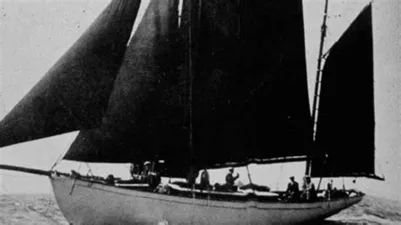

And like Erskine Childers, I used the Frisian Islands in my story, and the islands and sheltered seas of the West coast of Denmark. In homage to Erskine Childers, perhaps, I chose to use a traditional wooden gaff-rigged ketch as the iconic vessel, Der Sturmtaucher (The Shearwater in English), the type of vessel that would have been numerous when he wrote The Riddle of the Sands, and similar to Asgard, the last yacht he owned. They were both , Colin Archer ketches, designed as rescue boats for the fishing fleets of Norway.

But there’s more to it than that. Robert Erskine Childers was a remarkable man, and his story has far greater depth to it than just his writing.

Childers was born in London, in 1870, to a well to do family, but his father died when he was six years old from Tuberculosis, and his mother passed away six years later. He was sent to his mother’s family on their estate in County Wicklow, Ireland, and along with his four siblings, was treated kindly and grew up loving the countryside of Ireland, as part of the privileged protestant ruling class. He was admitted to Cambridge university on finishing school, and edited the Cambridge Review. Although his cousin, Hugh Childers, worked tirelessly for Irish home rule as a member of the British cabinet, at this point Childers argued vehemently against it in the college debating society.

On leaving university, he became a parliamentary official, with the intention of one day following his cousin into the house as a member of parliament. A sciatic injury sustained as a teenager precluded him from most sports, so he took up sailing, and bought a little yacht, Shulah, which he sailed alone in and around the Thames Estuary, but he sold her, and over the next years, the yachts he owned and sailed grew a little larger and more capable, until he purchased Vixen, a 30-foot cutter in 1897 and sailed her across the North sea to the Frisian Islands, in Holland and Northern Germany, which he repeated over the following few years. It was these voyages that became the inspiration for The Riddle of the Sands.

His sailing was interrupted in 1898 when he joined up to fight in the Boer War, where he was involved in a few significant engagements, but was evacuated from the front line with severe trench foot, and spent a few weeks in hospital in the company of a group of soldiers from Cork, who had enthusiastically signed up to fight with the British, and who were firmly against the growing calls for home rule.

He began writing The Riddle of The Sands in 1901, and it was published in 1903, almost immediately becoming a best-seller. It was largely based on his sailing experiences around the Frisian Islands and predicted the war with Germany and urged that Britain should prepare. It was an influential book – Churchill later claimed that it was a major factor in the British Navy expanding its naval bases in Scotland, at Scapa Flow, Invergordon, and Rosyth.

On a trip to America after the book’s publication, he met American heiress, Molly Osgood, a well read woman with Republican leanings. When they married in 1904, the bride’s father had a 28-yacht, Asgard, built as a wedding present for the couple, and again they cruised to the Frisian Islands. Gradually, Molly’s influence wore down his belief in Britain’s imperial policies, especially in Ireland and South Africa.

Childers was critical of British tactics in the Boer war in a volume of The Times History of the War in South Africa, and he was also scathing about the outdated strategy of the British Army, with the threat of war with Germany looming. It brought him unfavourable attention from the British military establishment. In retrospect, his criticisms were insightful and General Haig’s rejection of them ultimately added to the carnage of WW1.

By 1910, the Erskines had three children, although Henry, their second son, died before his first birthday. By then, his political stance with regard to Ireland had almost completely reversed, and he became a staunch advocate for Irish home rule, writing a book setting out its framework in 1911. The growing power of Ulster Unionism and its unwillingness to even consider home rule for the much wealthier and industrialised northern counties of Ireland made this an almost impossible ambition, and Childers became increasingly frustrated, especially when the Liberal Party, which he’d joined because of its support for Irish home rule, began to backtrack, with talk of excluding some or all of Ulster from their plans.

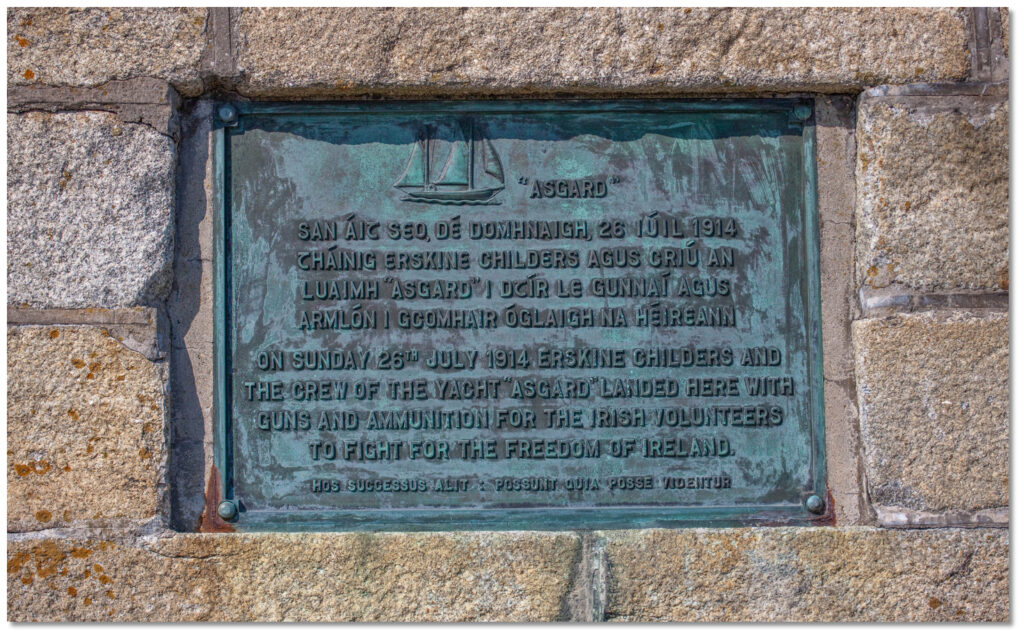

In response to the Ulster Unionists arming themselves with rifles, Childers’ support for Irish Home Rule dramatically deepened, and he used Asgard, his last and most famous yacht, to smuggle guns to nationalist fighters in Ireland. The vessel is now exhibited at The National Museum of Ireland.

A bill passed to enable home rule in 1914 was shelved for the duration of the 194-18 war and, despite his support for Irish Nationalism, he volunteered and fought for Britain during the war, earing a Distinguished Flying Cross. A violent crushing of the Irish Easter Rebellion in 1916 hardened Childers attitude to the British Government and, on being demobbed in 1919, convalescing from a severe attack of influenza, he met with the Sinn Féin leadership in Dublin. In 1921 he was elected as a Sinn Féin member to the Irish Dáil, but lost his seat in the 1922 General Election.

When negotiations for the Anglo-Irish Treaty returned a watered down home rule, Ireland was plunged into a civil war, intensified when Michael Collins, the Sinn Féin leader, was assassinated. Childers held various posts with in the Irish Republican movement but was never fully trusted, and was eventually marginalised. He disagreed vehemently with the Treaty’s insistence that the new Irish parliament should pledge allegience to the British King.

During the Irish civil war, he was arrested by the new Irish State he’d campaigned tirelessly for and tried for possession of a firearm, ironically gifted to him by Michael Collins, in contravention of the emergency powers resolution. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. An appeal launched by his lawyer was not heard by the time he was executed by firing squad, at Beggars Bush Barracks in Dublin. Before his execution, he shook the hands of the men who would shoot him and, in his last meeting with his 16-year-old eldest son, Childers he told him find and make peace with every man who had signed his death warrant.

His final words were to the firing squad, when he told them it would make it easier if they took a step closer.

Erskine Hamilton Childers, Childers’ son, went on to become the fourth president of Ireland.

And the mud flats, the sandbanks, the creeks and the marshes of Denmark and Northern Germany found their way into the Sturmtaucher Trilogy.